Teaching a Protein Language Model to Speak "Immune"

February 2026

A walkthrough of our MLCB 2025 paper on continued pre-training of protein language models

for pMHC-I binding prediction — why we did it, how it works, and what surprised us.

Teaching a Protein Language Model to Speak "Immune"

Here's a fact that keeps immunologists up at night: your immune system has to figure out which tiny protein fragments (peptides) sitting on the surface of your cells are "self" versus "intruder." This recognition happens through a molecular handshake between peptides and MHC class I molecules — and it's the foundation of how your body fights cancer. If we could predict which peptides bind well to which MHC molecules, we could design better cancer vaccines and T-cell therapies. The problem? There are roughly 30,000 known HLA alleles (the human version of MHC), and for most of them, we have almost no experimental binding data.

This is the problem that led me, along with Ariel and Nilah, to ask a deceptively simple question: can we take an off-the-shelf protein language model — one that already "understands" proteins in general — and teach it to specialize in the language of immune recognition?

The Intuition: Language Models Already Know Proteins

Large protein language models like ESM Cambrian have been trained on millions of protein sequences. They've learned a kind of grammar — which amino acids tend to appear together, what patterns form functional domains, how evolution shapes sequence diversity. Think of it like a model that's read every book ever written. It understands English really well. But if you need it to write radiology reports, it would help to let it read a bunch of medical literature first, right?

That's exactly what continued pre-training is. We took ESM Cambrian (300 million parameters, 30 transformer layers) and gave it a reading list of HLA-associated peptides from the IEDB — the main repository of immune epitope data. The model didn't get any labels at this stage. It just learned to fill in masked amino acids in peptide sequences, the same masked-language-modeling trick that made BERT famous. The idea is that by seeing thousands of peptides in the context of their MHC partners, the model would internalize the subtle patterns of what makes a peptide "MHC-compatible."

The Key Insight: When Does This Actually Help?

Here's what surprised us. The benefit of continued pre-training wasn't universal — it depended on how much labeled data you had for a given allele. We found a clear sweet spot:

For alleles with very few measurements (under 500 peptides), the continued pre-training didn't help much. The model simply didn't have enough downstream examples to leverage its new knowledge. For alleles with moderate data (500 to 2,000 peptides), continued pre-training gave us a boost of about 0.10 in Spearman correlation — a meaningful jump in this field. And for data-rich alleles (over 4,000 peptides), the gains leveled off because there was already enough signal in the fine-tuning data.

That moderate-data regime is exactly where most clinically relevant alleles live. So the technique lands where it matters most.

A Deliberate Choice: No Mass Spec

One decision we were pretty deliberate about was training exclusively on IC50 binding affinity data from functional assays and completely avoiding mass spectrometry data. Mass spec datasets are huge and tempting, but they systematically over-represent peptides with canonical anchor residues. They tell you what was easy to detect, not necessarily what binds. By sticking to quantitative IC50 measurements — log-transformed and rebalanced — we traded quantity for quality. And it paid off.

How Did We Do?

When we benchmarked against state-of-the-art tools on a held-out test set of peptides deposited in IEDB between 2020 and 2025, our model (ESMCBA) achieved a median Spearman correlation of 0.62 across 25 common HLA alleles. For comparison, NetMHCpan 4.1 — the field's workhorse, an ensemble of 50 networks trained on over 13 million data points — scored 0.56. MHCflurry came in at 0.49. We also outperformed NetMHCpan on distinguishing low-affinity binders from intermediate-affinity binders (AUROC 0.95 vs. 0.84), which is arguably the classification that matters most for therapeutic peptide selection.

Not bad for a single model with some targeted reading.

So What Does This Mean?

The broader takeaway is pretty encouraging: you don't always need a massive domain-specific dataset or a bespoke architecture. Sometimes, modest and targeted continued pre-training on a strong foundation model can get you surprisingly far. Going forward, we're excited about extending this to MHC class II, incorporating structural features, and exploring whether these adapted representations can help with the even harder problem of predicting immunogenicity — not just whether a peptide binds, but whether it actually triggers a T-cell response. That's where the real clinical impact lives.

This work was accepted at the 20th Machine Learning in Computational Biology (MLCB) meeting.

What If We Could Design Immune Peptides from Scratch — Using Physics Instead of Data?

February 2026

A walkthrough of our ICML 2025 workshop paper on generating pMHC-I libraries

with diffusion models — the dataset bias problem, our structure-first approach,

and why existing predictors completely failed on our designed peptides.

What If We Could Design Immune Peptides from Scratch — Using Physics Instead of Data?

If you've been following the MHC binding prediction space, you've probably noticed a pattern: everyone trains on the same datasets, benchmarks on the same test splits, and reports incremental improvements. But there's an uncomfortable question lurking underneath all of this — what if those datasets are biased in ways that make our models look better than they actually are?

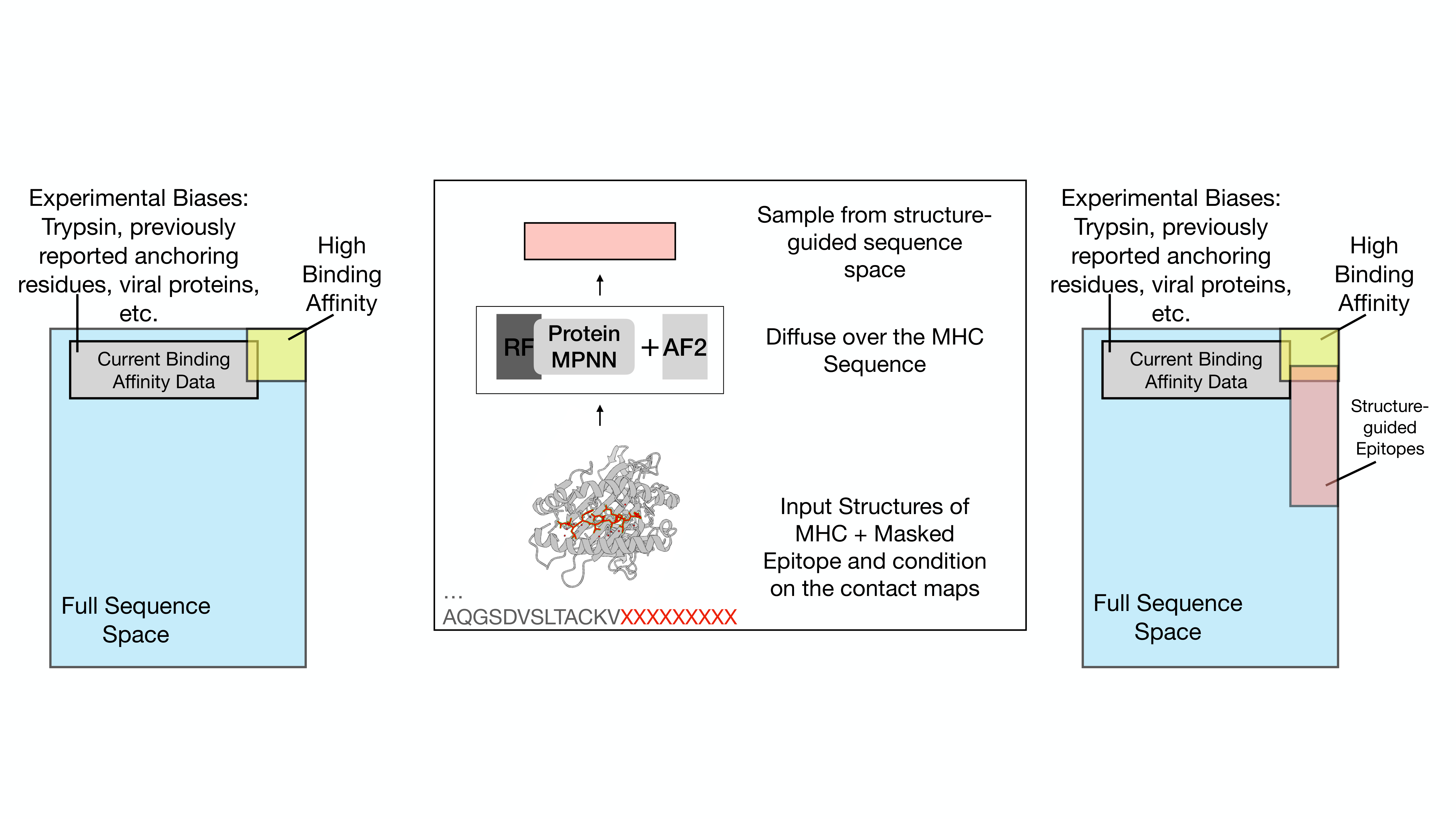

That question is what drove this project. Together with Ariel and Nilah, we set out to build a benchmark of MHC-binding peptides that doesn't come from the usual experimental pipelines. Instead, we designed peptides from scratch using diffusion models conditioned on crystal structure geometry. The goal was to create peptides that should bind — based on physical structure — but that no existing model has ever seen during training.

The Problem with Current Benchmarks

Most of the peptide-MHC data we have comes from mass spectrometry experiments or binding assays. These methods are fantastic, but they have blind spots. Mass spec systematically under-detects certain peptides (cysteine-containing ones, for instance) and over-represents peptides with strong canonical anchor residues. When you train a model on biased data, you get a model that's great at recognizing the patterns in that bias — and not necessarily great at recognizing genuine binding.

It's like training a food critic exclusively on Italian restaurants and then asking them to evaluate Thai food. They might still have good instincts, but you wouldn't fully trust the score.

Our Approach: Let the Structure Do the Talking

Here's the idea. We have about 119 high-resolution crystal structures of peptide-MHC complexes sitting in the Protein Data Bank. These structures show us, at atomic resolution, exactly how peptides nestle into the MHC binding groove — which residues make close contacts (within 3.5 angstroms), which ones form looser associations (3.5 to 5.0 angstroms), and where the anchoring happens.

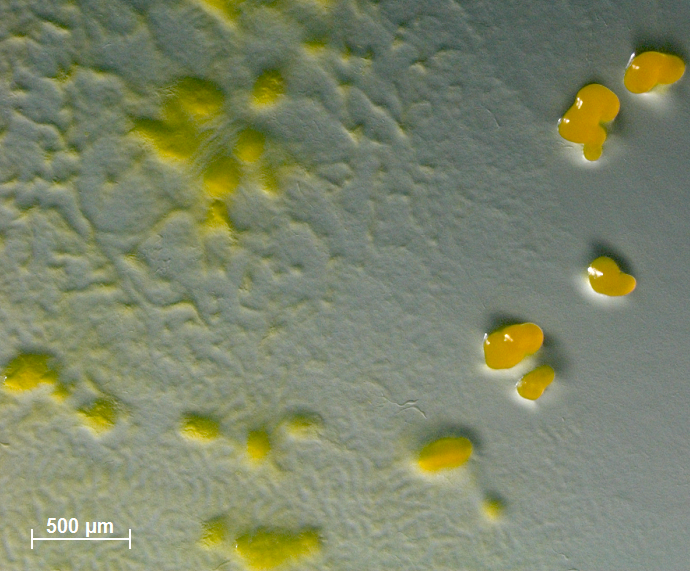

We used these contact maps as conditioning constraints for RFdiffusion, a structure-generation diffusion model. The process works like this: we take an MHC crystal structure, rip out the peptide, and ask RFdiffusion to hallucinate a new peptide backbone that fits the groove. We run 50 diffusion steps, generating backbones for peptides of 9 to 11 residues. Then we hand those backbones to ProteinMPNN, which designs 64 amino acid sequences per backbone and ranks them by fit. Finally, we fold every designed peptide-MHC complex with AlphaFold2-Multimer and filter for structural confidence — keeping only designs where the peptide pLDDT hits at least 0.80.

The result is a library of computationally designed peptides spanning 27 HLA alleles that should be structurally compatible with their MHC partners, but that were never derived from any experimental binding dataset.

The Fun Part: Breaking Existing Predictors

This is where things got really interesting. We took seven state-of-the-art binding predictors — NetMHCpan, MHCflurry, HLApollo, HLAthena, MixMHCpred, MHCnuggets, and our own ESMCBA — and asked them to distinguish our structurally designed peptides from experimentally validated strong binders. If these predictors truly understand MHC binding, they should score our well-designed peptides similarly to known binders.

They didn't. AUROCs ranged from 0.03 (MHCnuggets) to 0.19 (HLApollo). That's essentially random or worse. The same predictors scored above 0.88 when discriminating validated binders from random peptides — so they're not broken in general. They just can't recognize binding potential in peptides that look different from their training data.

This is a big deal. It means there are entire regions of peptide sequence space that are structurally plausible binders but invisible to current tools.

Sanity Check: Do the Designs Make Biological Sense?

We were careful to check that our diffusion pipeline wasn't just generating nonsense. When we looked at anchor residue preferences, the designs reproduced known biology beautifully. For HLA-A*02:01, we saw the expected Leucine enrichment at position 2 and Valine at the C-terminus. For HLA-B*57:01, the signature Tryptophan anchor at the C-terminus showed up clearly. And peptides with proper anchors had significantly higher AlphaFold2 confidence scores — so the structural validation and the sequence motifs aligned perfectly.

Why This Matters

We see this resource serving two purposes. First, it's an unbiased benchmark. If you're developing a new binding predictor, you can test it against these structurally designed peptides to see whether it's truly learning binding physics or just memorizing dataset patterns. Second, these libraries represent a starting point for discovering genuinely novel peptide ligands — candidates that existing methods would overlook but that might make excellent vaccine targets or therapeutic leads.

Next, we want to incorporate T-cell receptor constraints into the design pipeline — because binding to MHC is only half the story. The peptide also has to be recognized by a T-cell receptor to trigger an immune response. That's the real frontier.

This work was accepted at the 2nd Workshop on Generative AI and Biology at ICML 2025.